- Home

- Tickner, Robert;

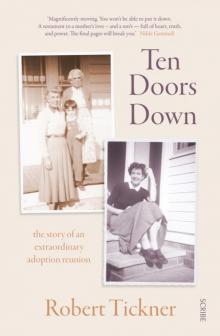

Ten Doors Down

Ten Doors Down Read online

TEN DOORS DOWN

Robert Tickner grew up a country boy on the New South Wales mid-north coast and became an Aboriginal Legal Service lawyer and an alderman of the Sydney City Council. In 1984, he won the federal seat of Hughes, and, in 1990, he became the federal minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs, in a period of great reform during the Hawke and Keating governments. He has been Australia’s longest-serving minister in that role. He then became CEO of Australian Red Cross and led the organisation for a decade from 2005 to 2015.

Scribe Publications

18–20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

First published by Scribe 2020

Copyright © Robert Tickner 2020

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

This text includes excerpts from Kenny, P., Higgins, D., Soloff, C., & Sweid, R., Past adoption experiences: National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices (Research Report No. 21), Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, 2012.

9781925849455 (Australian edition)

9781925938227 (e-book)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

scribepublications.com.au

In writing this book, I expressly honour my adopted parents and my birth parents, my stepmother and stepfather, and my four wonderful sisters and brothers, who all became such a special and ongoing part of my life. And to my daughter, Jade, and son, Jack, for their contribution to the events described here. This book is dedicated to all of them.

Surplus from the sales of this book will be donated to the Justice Reform Initiative to support the growing campaign in Australia to reduce our reliance on outdated, expensive, and ineffective prisons, which will make our communities stronger and safer.

justicereforminitiative.org.au

Contents

Prologue

1. Birth and adoption

2. Father Bert and Mother Gwen

3. Leaving the nest

4. Moving into politics

5. Sydney City Council

6. Losing my father

7. Beautiful Baby Jack

8. First steps towards meeting my birth mother

9. Learning more about my birth mother

10. Adoption practices in New South Wales in the 1950s

11. The Stolen Generations

12. Meeting on the Sydney Opera House steps

13. Learning my birth father’s name

14. Giving in to temptation

15. Grieving for Mother Gwen

16. An exchange of letters

17. Meeting my birth father, brothers, and sisters

18. Big life changes

19. Nature or nurture?

20. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Prologue

I have a date with destiny this Sydney summer day in late January 1993.

I have always moved fast when I’m on a mission. Today, I am truly a driven man, but, at the top of the historic sandstone stairway leading to the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney, just along from the Art Gallery of New South Wales, I pause to gather my thoughts.

Sydney Harbour, which Captain Arthur Phillip aptly described as ‘with out exception the finest Harbour in the World’, is awash with sailing boats, ferries, and pleasure craft of all kinds. Down below in the gardens, people are relaxing and enjoying the sparkle of the water, unaware of and indifferent to what is about to happen to me.

Electrified, brimming with optimism, I am catapulting down the steps into the gardens, where I soon find myself mingling with the families and couples strolling along the long arc of the stone wall that circles the harbour and leads to the Opera House. All around me are people in the Australian summer uniform of colourful shirts, dresses, shorts, and thongs. By contrast, I am dressed up for the occasion in a white shirt and casual pants. I want the person I’m meeting to know I’ve made an effort, but don’t want to scare her with the formality of a suit. I have put a lot of thought into all aspects of today, including this simple decision of what to wear. There are so many small details to get right. I will only get one shot at this encounter and want to make it special in every way.

As I’m walking, I can’t help but notice the many babies in prams and little kids with their families along the footpath. Given the nature of my fast-approaching meeting, these sightings are quite unnerving, and my edginess and anticipation of what is to come continue to mount.

When the white sails of the Opera House appear, I pull my shoulders back and stride out. I feel so strong now, I could tow a bulldozer behind me.

I run up the Opera House steps to get the best view of the surrounding area. I am early, as planned; lateness might have conveyed a lack of caring or indecision on my part, so it wasn’t an option. I can see way into the distance in both directions, and I am confident that I will be able to see my rendezvous companion long before she sees me.

It’s only then, looking around, that I realise the Opera House forecourt is unusually busy. Some huge and colourful carnival tents have been set up right in front of the steps, an unwelcome intrusion I hadn’t anticipated when it was agreed we meet here. I hope the additional crowds won’t cause any confusion. I know the person I’m soon to meet will be feeling petrified, so I want everything to run as smoothly as possible.

In the days preceding, I haven’t had much time to dwell on this meeting, but now, the magnitude of it is sweeping over me. I peer into the distance trying to make out who is approaching, but my eyes are too watery to see anything properly. I realise I must be quite a sight: a 41-year-old man standing alone at the top of the Sydney Opera House steps, tears streaming down his face. Crazy thoughts spin in my head; suddenly, I see the carnival tents as a sign of our future together, full of happiness and laughter.

I pull myself together, and peer into the distance again. Will we hug? I wonder. Yes, definitely. But what if she comes up behind me? I experience a little staccato of panicked thoughts when I realise that, although we have seen photographs of each other, photographs sometimes lie. What if I don’t recognise her? We have never met. I have never heard her voice.

Our scheduled meeting time is now only minutes away. I take deep breaths, and try to meditate to stabilise my roller-coaster of emotions. For some reason, my sensory awareness of everything around me is heightened. I see a solitary older woman about 400 metres away, coming from the direction of Circular Quay. Could that be her? No, a false alarm. And then another — and another. By now, my heart is in my mouth.

I see another figure even further away, but this time, I know instantly it is her. I take a photograph with the cheap throwaway camera I purchased, as an afterthought, on the way to the city this morning. Later, I will show her this photograph, and all we will be able to see is a tiny speck in the distance, barely visible. But I knew it was her, as soon as I saw her.

As the minutes tick by, the speck gradually becomes a tall handsome woman. She stops at the bottom of the crowded Opera House steps, and I bound crazily down towards her, like a man possessed. I startle a Chinese tourist standing between us as I hurtle in her direction, waving vigorously at the person just behind her. She moves out of my way just in time.

‘It’s me, it’s me, it’s me!’ I shout, pointing at my ch

est with my fingers.

The woman looks up and sees me, and a broad smile spreads across her face.

We are swallowed up in each other’s arms, weeping, laughing, and hugging in a flood of emotion.

I have met my birth mother, Maida, and she is holding her only child in her arms for the first time since the week I was born, 41 years ago.

1

Birth and adoption

I was born at 1.25 am on Christmas Eve 1951 at Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Surry Hills, an inner-city suburb of Sydney on the doorstep of the central business district. Once disparagingly dismissed as a working-class slum, Surry Hills has now morphed into one of the most upmarket residential areas in Australia. Even the hospital site has been recast into a trendy residential and commercial complex, but, for many decades, it was a major maternity hospital, responsible for some of the worst practices in baby adoption in the nation.

My mother, Maida Anne Beasley, was 23 years old at the time of my birth and not married. She had grown up in the New South Wales central-west town of Orange, and had come to Sydney for my birth. As did almost all single women who became pregnant in those times, she suffered family and social pressures to leave her work, her town, and her friends. She carried the shame of her pregnancy to the city of Sydney, where she secretly gave birth to her child.

After my birth mother had signed the papers to give the child up for adoption, she was told nothing at all about where her baby had gone. The signing completed, that was the end of the matter; the law had spoken. The prevailing thinking at the time was that an adopted baby should be given a fresh beginning, free of the stigma of illegitimacy. Adopting parents were encouraged to think that the child they were taking home was unwanted by the birth mother. It took decades of campaigning for relinquishing mothers to gain public awareness and understanding of their pain.

I was given a new identity, and all doors were firmly shut between my birth mother, my wider family, and me until the law changed in New South Wales some 40 years later. Being a sensitive, kind, and loving person, my adoptive mother, Gwen, must have given some thought to what my birth mother would have been feeling, but, in those days, no contact with an adopted child’s birth mother was possible. The whole process was shrouded in confidentiality and secrecy.

The Adoption Order of the Supreme Court of New South Wales is a formal, legalistic document. Mine began ‘In the matter of David John Beasley (to be known as Robert Edward Tickner) in the matter of the Child Welfare Act 1939, Part XIX’ and was dated Thursday 24 April 1952, almost four months after my new mother and father ‘took delivery’ of me in December 1951. The final adoption order was made by Judge Dovey of the New South Wales Supreme Court, who became better known to many Australians in later years as the father of Margaret Whitlam, wife of prime minister Gough Whitlam. It notes various affidavits of departmental officials and those of Bertie Robert Tickner and Gwendoline Daisy Tickner, my new parents.

Gwen and Bert took me from the hospital to Gwen’s mother’s house at 18 Lansdowne Street, Merrylands, a suburb of western Sydney. Without a doubt, I was a very welcome addition to the family. My mother and father were both in their early forties and, despite marrying in their twenties, had not been able to have any children of their own. This wasn’t something my parents ever discussed with me, but, as a child, I came to piece it together through fragments of overheard conversations. I don’t know why they hadn’t been able to conceive, and perhaps they didn’t know themselves, given the limitations of medical science at the time, but their strong desire for a child was certainly why they turned to adoption.

To say I was showered with love by my mother and father is a massive understatement. When I look at the photographs of Gwen, my mother, gazing besottedly at her tiny new baby, and later her young child, I can feel the love emanating from them. I often think about what it must have been like for her in those early days of my life, as it’s plain to see she must have wanted a child so much. I vividly remember her saying to me often as she got older, ‘I cannot imagine my life without you. Your arrival completely transformed my life.’

At the time of my adoption, my mother and father were living in Forster, a sleepy seaside town some 300 kilometres north of Sydney. They’d moved there in 1949 with the intention of semi-retiring, or at least adopting a slower pace of life, even though they were not yet 40 years old. They had met in their late teens through my dad’s younger sister, Dorrie, who was a tennis-playing partner of my mother, and, within a few years, they had married at St John’s Anglican Cathedral in Parramatta.

Forster and its twin town of Tuncurry were little more than tiny fishing villages in the 1950s, with a bridge yet to be built across Wallis Lake. The only access was via a punt operated by the Blows family. I guess, on reflection, my mother and father were very early pioneers of the sea-change movement, in that they left a prosperous city business — a sporting goods and piano store in Parramatta — to take up a new life in this small seaside spot with a combined population of approximately 1,500–2,000 people. Dad had ideas of living a semiretired fishing life and operating a boatshed as a hobby, which he did in his early years in Forster. My parents had been the mixed doubles tennis champions of Western Sydney before they moved to Forster, and had planned to play more tennis in their new country home, but they were unable to find many people to play with in this little coastal fishing village.

They lived in a white two-storey weatherboard home at 14 Lake Street, inadvertently located directly opposite both the Forster Catholic church and the local masonic lodge. It must have been one of just a handful of two-storey houses in the town at that time, and it still stands, but has been moved forward on the block and become part of the Ingleburn RSL holiday units. The house was built not long before I arrived in Forster, and, now I think about it, the second upstairs bedroom was probably waiting for the arrival of the new baby.

There was a huge backyard, with a cottage at the rear that my parents rented out, when it wasn’t being used by visiting friends and family. Also at the back of the house was a huge tiered stand supporting a giant tank. The tank supplied our household water as there was no proper town water supply at that time. Down the path was the pan toilet, and, in the early years, the nightsoil cans were hand-collected by a heroic and dedicated council workforce. From those years as a small boy, I can still remember the stench of those collection days!

We lived in the heart of town, four blocks from the local ocean pool, two-and-a-bit blocks from my beloved Pebbly Beach and the lake, and about seven blocks from the local high school. I walked, and later rode my bike, everywhere, often not bothering to wear shoes unless reminded. It was the perfect place for a child to grow up. I felt I knew pretty much everyone in the town and certainly greeted anyone I saw on the street in a warm and friendly manner. My childhood in Forster was idyllic in many ways. My parents were quite strict, but, whenever I return to my earliest memories, I can only evoke the swelling pride and love they showed me. For my mother, in the fortieth year of her life, I was a gift from heaven.

Even in their early years in Forster, my parents were highly respected people. They must also have been the talk of the town with their sudden new baby. In a small country town, where everybody knew everybody, there were few secrets, and the fact that I was adopted was never hidden from me. Ever since I can remember, I have always known and never had the slightest concern about it. My mother told me I was ‘chosen’ by her and my dad, and that was good enough for me as a child. I believed it without question. As my parents intended, I got the feeling I was lucky, because, while other kids just were born to their parents, my mum and dad chose the child they wanted. I felt greatly loved and appreciated as their child, which is what most of us want. This I truly believe. For a child, being and feeling loved is one of the bedrocks on which their future life is built.

I do remember one occasion, probably when I was about ten, when there was a fleeting conversation w

ith my mum about my adoption, and she proffered some very basic information about my birth parents, although she didn’t refer to them as that. The name ‘Beasley’ was mentioned, and something was said about electricity or electrical engineering. Clearly in my own mind I didn’t need any more information at that time, as I was growing up with such a loving and supportive mum and dad.

For my part, I was fiercely proud of my adoption. All my mates knew I was adopted, and I can’t recall it being mentioned much by any of them, if at all — or at least not that I was aware of. In my early years of high school, I did once think I heard a classmate say something derogatory about my adoption. I know now that I completely misunderstood the incident, but at the time I became so upset and furious that I refused to talk to him for a long time, which was some feat in a class of about 30 kids who saw each other almost daily. We eventually patched things up and remain close mates.

I had asthma as a small child, so my parents encouraged me to take up competitive swimming at the age of six as a way of building my lung capacity. My father took on the role of coaching me, along with dozens of local kids. He approached the task in a very scientific way, reading widely and attending coaching clinics conducted by Forbes Carlile in Sydney. Perhaps he needed all the help he could get as he couldn’t swim a stroke himself! The main training pool was Forster ocean baths, a 50-metre saltwater pool, and I could ride there on my bike in five minutes. It still gives me the horrors when I remember diving into the often chilly water, especially as winter approached. As a tall scrawny kid without an ounce of fat, I was particularly vulnerable to the cold. I always aimed to swim in Lane 6, closest to the wall, rather than Lane 1, which was exposed to the vast icy expanse of the main pool and was like being banished to Siberia. On the other hand, in the summer, when fresh water might not wash in from the ocean for weeks on end, the pollution in the pool could become intolerable.

Ten Doors Down

Ten Doors Down